After six months of work on this project, I finally have my first set of data. In this post, I want to reflect on what these data might tell us about people’s relationship with TikTok—and what they reveal about how we study the perception of this platform. It’s not just about what the data show, but also how we interpret them and what questions we should be asking next.

In my initial experiment, I collected valid data from 28 participants. Each participant watched the same set of videos on a computer with eye-tracker, presented in two formats: landscape and portrait. Before every session I made a note of participants’ screen time (TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube) – not through self-reporting, but by directly checking the screen time data on their phones.

After processing and analysing the data, we obtained interesting information about differences in fixation entropy, saccade directions, and, in general, the relationship between video format and stylistic elements in the context of perception. We are preparing academic outputs on all of this. But what surprised me the most was something else.

We were unable to measure any convincing effect of screen time on the way videos are watched. It even makes me rethink some of my hypotheses. But let’s take it step by step.

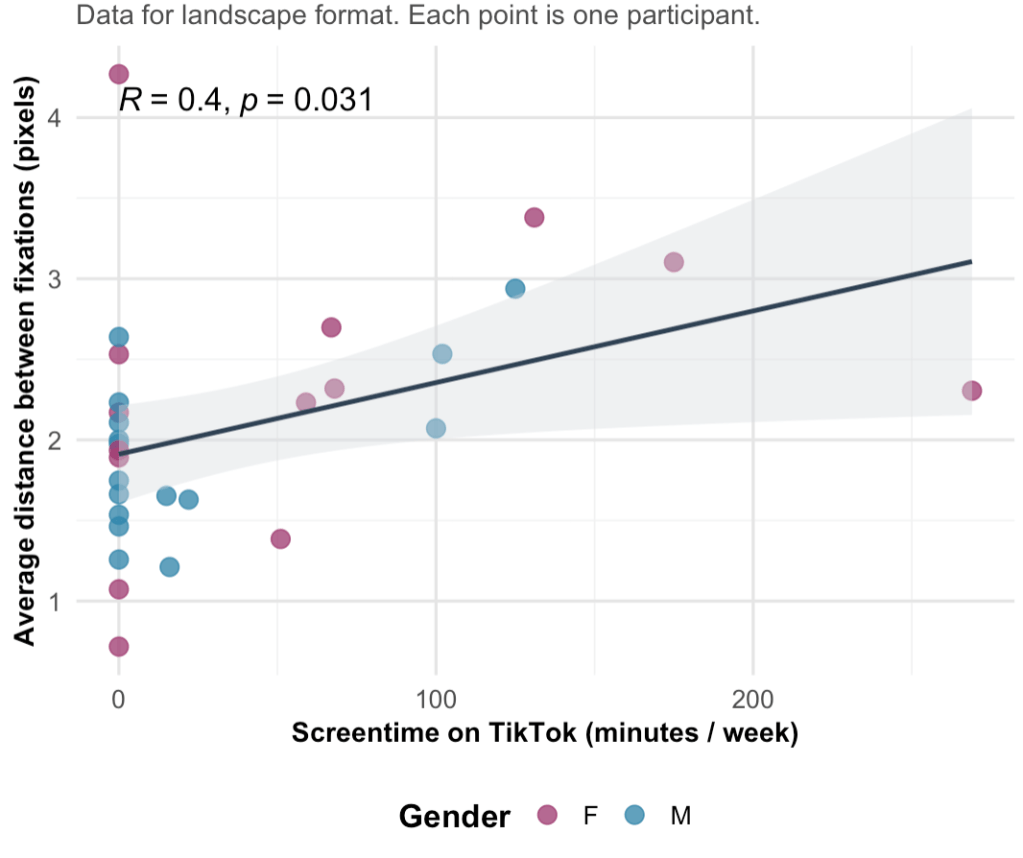

To be honest, I did find one statistically significant correlation. And it’s one that deserves a headline in the newspapers: TikTok makes you less focused when watching movies!

Sounds serious, right?

More precisely, we found that participants with higher average screen time on TikTok have a greater distance between fixations when watching landscape videos. In other words, if you watch a lot of TikTok and then watch a movie, your eyes will jump around more than the eyes of people who don’t watch TikTok.

Does it still sound serious?

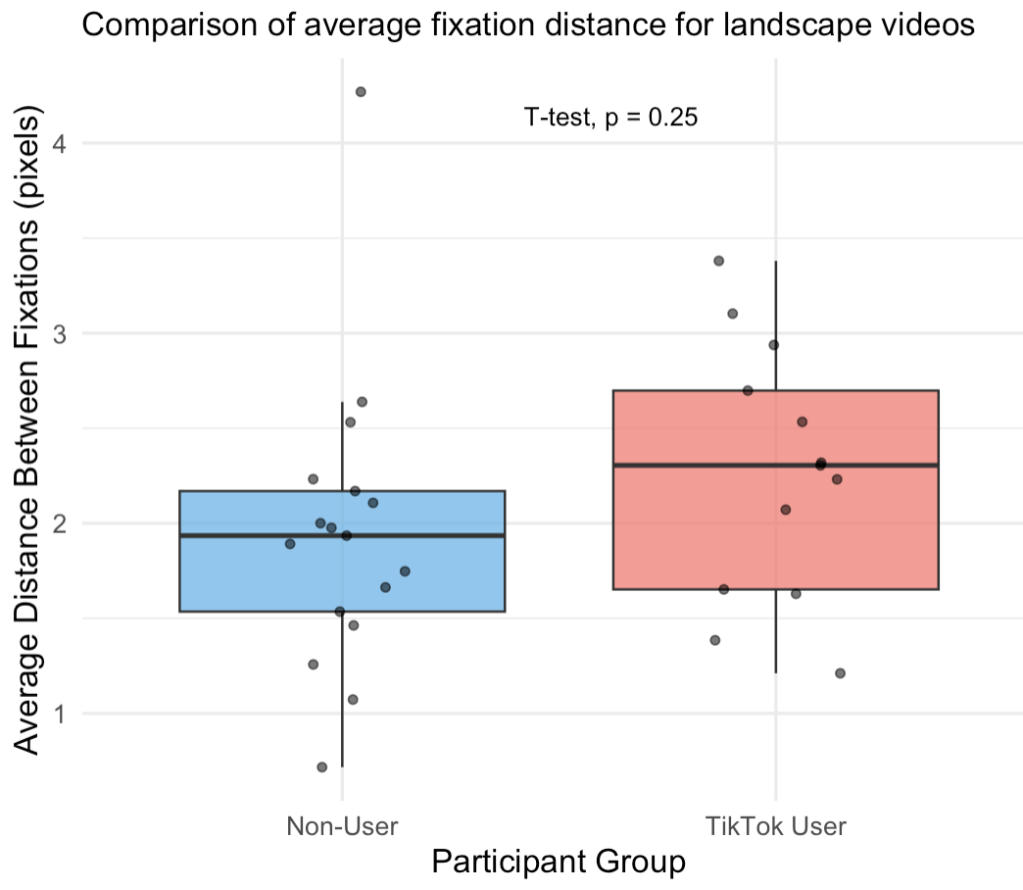

Take a look at the graph illustrating this effect. The p-value even shows that the effect is statistically significant.

Does it sound even more serious now?

Notice the dots on the y-axis that have zero screen time on TikTok. Let’s try visualizing the data differently to get two groups: TikTok users and non-users.

And suddenly, the effect is gone. Or at least it is so small and statistically insignificant that nothing can be said with certainty on its basis.

What happened?

Imagine that you collect a huge amount of data (fixations, saccades, pupil diameters, blinking… in the spreadsheet with more than 100 columns and calculate metrics such as entropy, dispersion…) and add to it other data from a questionnaire (age, gender, average screen time…). Then you just try to look for what correlates with what until you find that some correlation is statistically significant. In other words, you are committing fraud by randomly comparing data and looking for something that looks like positive result. And when you get a low p-value, only then do you formulate a hypothesis. This is called data fishing or p-hacking.

I was in the opposite situation. I measured the effect predicted by the hypothesis. The problem was that when I then explored other variants of correlations between screen time and eye-tracker data, I didn’t find any other statistically significant correlations. The one with screen time on TikTok and fixation distance in landscape videos was the only one. Sometimes it even showed me that higher screen time correlates with more focused fixations. The complete opposite.

These findings have led me to reconsider some of my initial assumptions. I originally believed that long-term exposure to TikTok would affect the way we watch films. But based on the current data, that effect is either not present or not captured by my experimental design. In any case, I don’t have sufficient evidence to claim that screen time directly influences how we watch videos. What’s more, I began to doubt whether it still makes sense to continue focusing on studying influence of screen time on viewing habits.