After almost a year, I was teaching students again. I was lucky that the Department of Theater and Film Studies gave me the opportunity to teach almost anything, so I was able to talk about my current research. Specifically, I decided to discuss with students the significance of the frame of a moving image.

Looking back, I don’t think I was ever particularly interested in the frame of a film. Of course, I was aware of pan-and-scan editing of films for television and VHS, but since I had been using the internet since childhood, it didn’t bother me that much. It was more of an trivia from history of cinema.

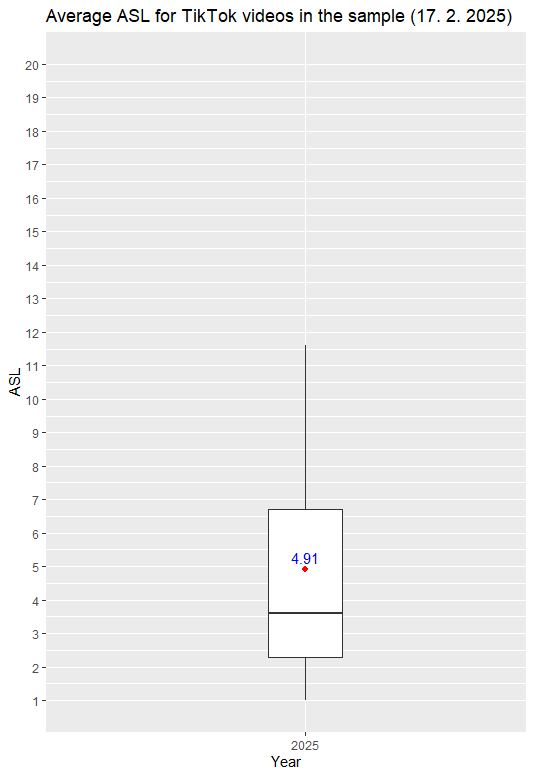

That changed, of course, with vertical short videos. If we look at the statistics, today’s TikTok users in Czechia watch an average of over an hour of videos in vertical format every day. That’s hundreds and hundreds of scenes, short stories, or just recordings of something.

In other words, today the frame of the film image is an essential topic. And that’s why I wanted to devote a seminar to it.

We started with a discussion of literature (Eisenstein: The Dynamic Square and Somaini: The Screen as “Battleground”: Eisenstein’s “Dynamic Square” and the Plasticity of the Projection Format) to raise awareness that the horizontal shape of the film frame was not always a given. The students then worked in groups to analyze several films that creatively manipulate the aspect ratio of the image. These included The Door in the Wall (1956), The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), X (2022), films by Ola Røyseland, and a selection of TikTok videos.

The culmination of the course was for students to work in small groups to shoot their own short film in which they tried to use the frame to influence the audience. To test whether they succeeded in their intention or not, each group had to write a hypothesis and email it to me before the final screening. In the discussion after the screening, I then tried to find out whether the authors’ intention was successful or not.

In my opinion, the course was a success. It seemed to me that the students used the knowledge they had gained from reading and analysis in their own work. And the resulting films turned out very well, even though the students only had one day to make them.

With their permission, I am presenting the films here.

Team 1 (Březnická, Raiskaia, Karim)

The students achieved something unprecedented in this video. Their intention was, of course, for the colored rectangles to draw the viewers’ attention. However, I noticed that after the first rectangle appeared relatively far from the center of the image, I tended to look around the edges of the image to see if there were any other colored rectangles. I had the impression that the students had managed to break the center bias that movie viewers naturally gravitate toward and that filmmakers take advantage of.

Team 2 (Podlaha, Hampeisová, Prajslerová, Ryšanková)

It was probably the most ambitious film in the class. Those of you who watched the video on your smartphone—did you turn your phone around? If so, you fulfilled the filmmakers’ intention.

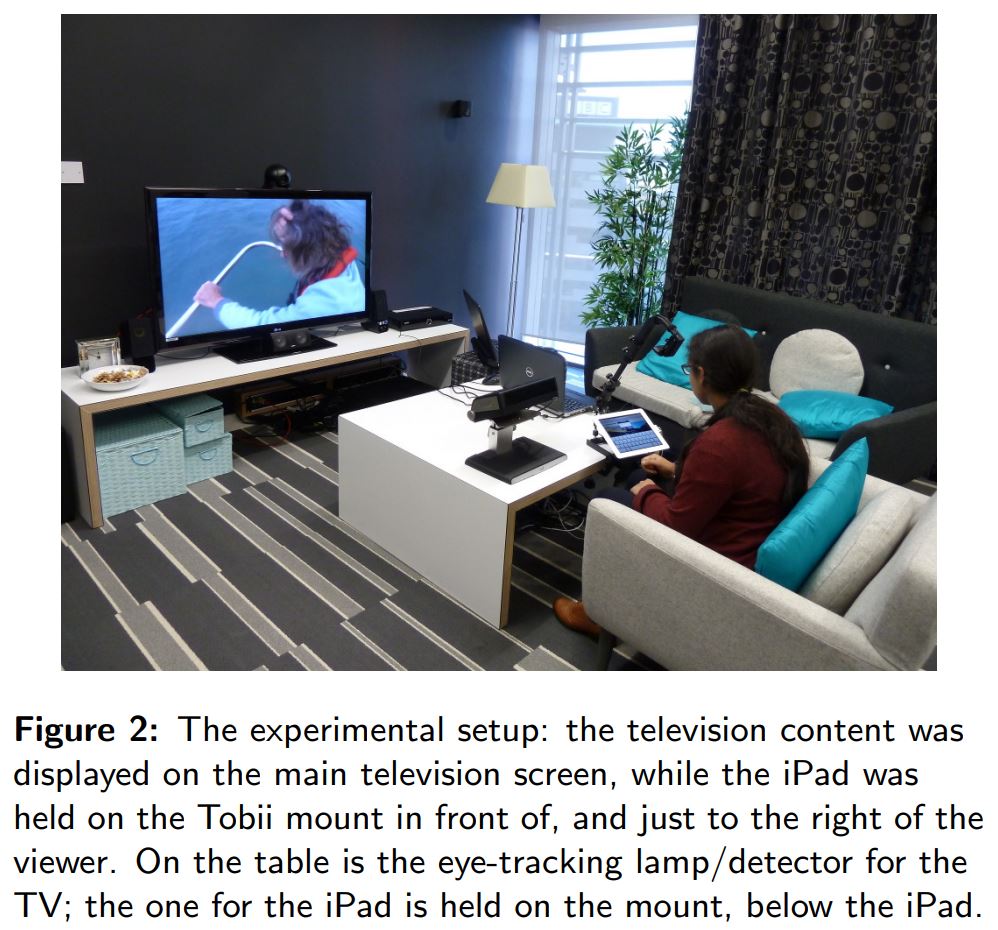

In the discussion after the screening, I repeatedly heard that it was the moment when the character was upside down that made them turn their phones. Whatever the moment, it shows us that watching audiovisual content on a smartphone can count and deliberately elicit active audience engagement that would have been unthinkable in a cinema.

Team 3 (Mührová, Tkadlecová, Moskvina)

The students attempted to assign different perceptions of time to different aspect ratios. Can you guess which aspect ration was supposed to represent hecticness? Probably yes. In any case, I assume that they did not rely solely on the aspect ratio, but also supported the state of being busy with movement, colors, and tripling the videos.

Team 4 (Salvadori, Mičola, Romsy)

In this film, the students devoted themselves to narration more than any other group. Working with the frame therefore does not come to the fore as it does in other pieces; it does not draw attention to itself. The frame of the image strives to be an organic part of the whole.

Team 5 (Cvrkalová, Kalianková, Kožárová )

The last group tried to create an impression of paranoia and surveillance in the audience. Judging by the reaction of their classmates, they were the only ones who didn’t succeed. I wondered why that was. The reason could be the short length of the film or the violation of certain editing techniques (e.g., the absence of a POV shot after a close-up of the face). Despite the fact that the students in team 5 did not succeed in fulfilling their intention, it was fascinating to see how they approached the task.