I often encounter the opinion that TikTok is fast. Frankly, I’ve never understood it. I could describe TikTok in a number of words, but speed would not be one of them. Maybe the problem is what we mean by speed.

The last time I came across the idea was in Berenike Jung’s “Travelling Sounds, Embodied Responses: Aesthetic Reflections on TikTok” from the anthology Traveling Music Videos edited by my colleague Tomáš Jirsa. Berenike Jung describes TikTok as follows:

“the videos’ short length creates an accelerated, hypnotic pace of viewing. The videos are themselves often accelerated and/or stuttering, edited to a speed that puts chaos cinema in the rearview mirror and further normalizes jump cuts as the rule for online videos”

I identify speed in three senses in the quote:

- the fast pace caused by the short length of the videos

- the acceleration of videos

- the use of jump-cuts to eliminate shots where nothing important is happening

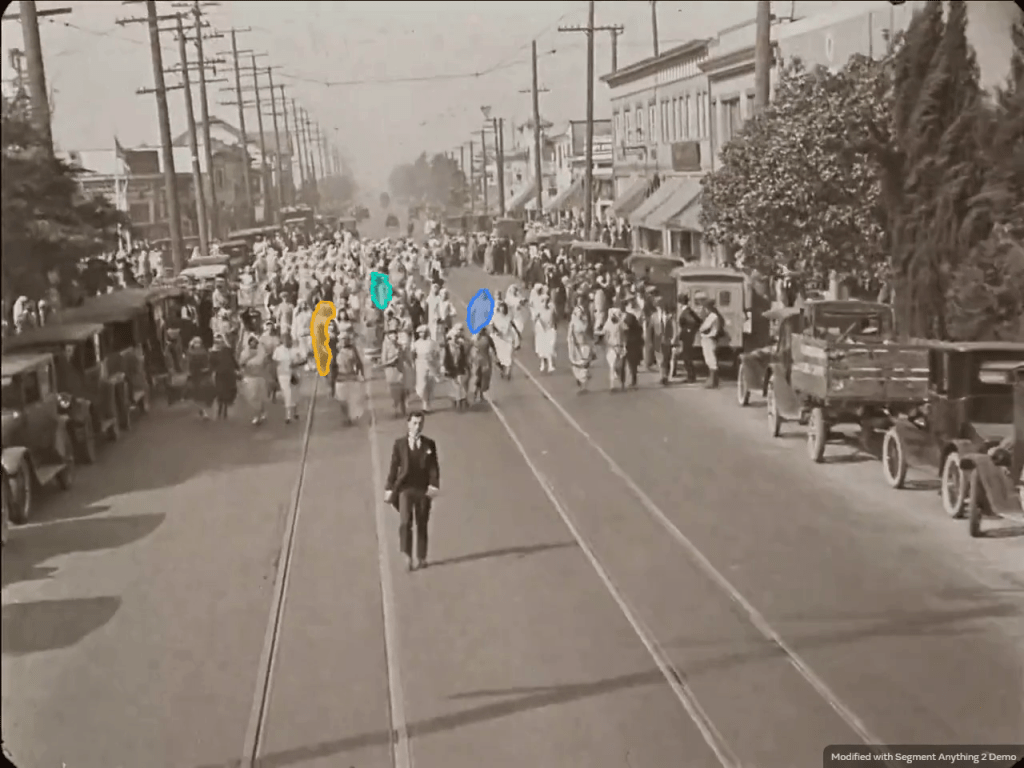

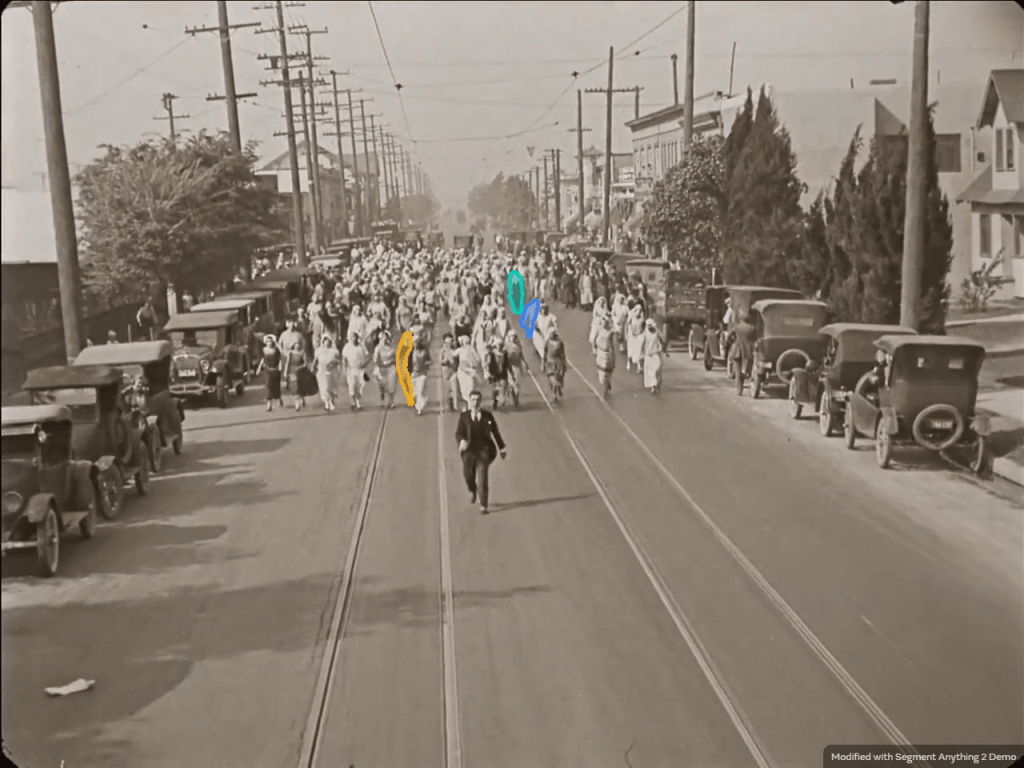

In at least two of these, it is something we have known for decades, so it hardly surprises any viewers today. Anyone who has ever watched a silent movie has encountered video acceleration (the reason for this is the different standard of projection speed expressed in terms of the number of frames of film stock per second of projection).

Similarly, the jump-cut cannot be considered anything groundbreaking. It is associated in film history books with Godard’s A bout de souffle (1960), but even that was not the first use. David Bordwell wrote an article on the jump-cut in 1984 (Wide Angle, vol. 6, no. 1) where he points out that the jump-cut had been used since the early era. In my notes, I found uses of the jump-cut in, for example, the Finnish film Valkoinen peura (1952, Erik Blomberg).

The remarkable speed of TikTok can therefore perhaps only be explained by the short length of the videos. And while we could find examples from the past (commercial breaks on TV, blocks of trailers and ads in cinemas before the screening starts, blocks of video clips on TV and YouTube), TikTok has at least contributed to shortening videos to a new level.

But the list of possible understandings of what makes TiKTok fast is not, in my opinion, complete. Leaving aside the contextual aspects of video production speed and TikTok’s speed of expansion. The impression of TikTok’s speed could still be caused by at least two things: 1. the average shot length of a TikTok video, 2. the amount of information conveyed through spoken word or text. Given complexity of the combination of spoken word, text in videos, text in subtitles, and text in the app interface, I’ll leave point 2 for another time. In the following lines, I will focus on the average length of a shot.

Average shot length is, in my opinion, a better indicator of speed than simply video length. Try to imagine a hypothetical social network where users could upload 30 second long videos, but only in one take. I dare to doubt that we would consider such a social network fast in any sense. We might even find it slow and boring. Especially compared to the US film and series, where the average shot length is between 3 and 5 seconds.

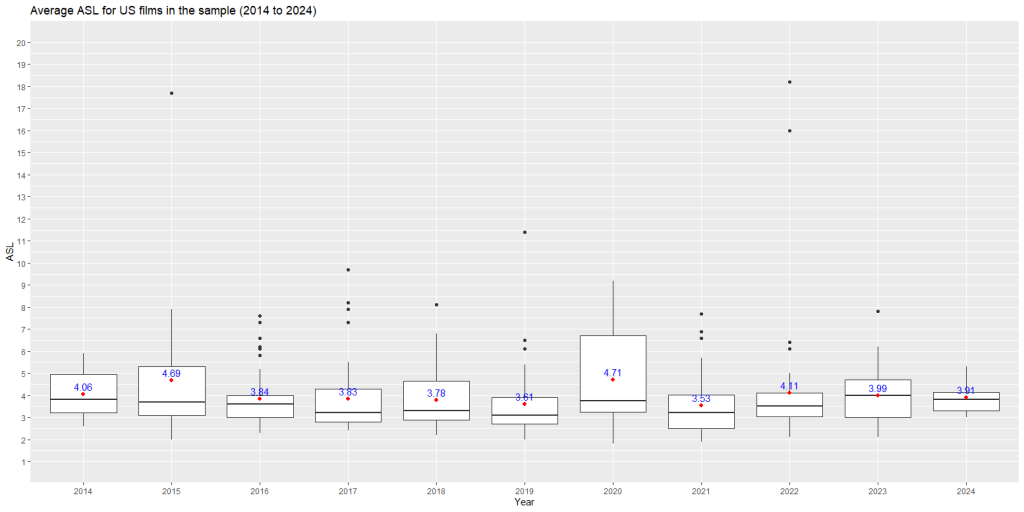

We can see this for ourselves thanks to Radomir Douglas Kokeš, who has been collecting data for a long time and publishing it on his blog. From his database, I was able to select a sample of films produced in the USA between 2014 and 2024 and calculate the variance of average shot lengths. I had 430 films and episodes in my sample. Sure, it’s not all that’s been produced, but better data just aren’t available.

The graph clearly shows that although the average shot length varies, it oscillates around similar values (average of averages).

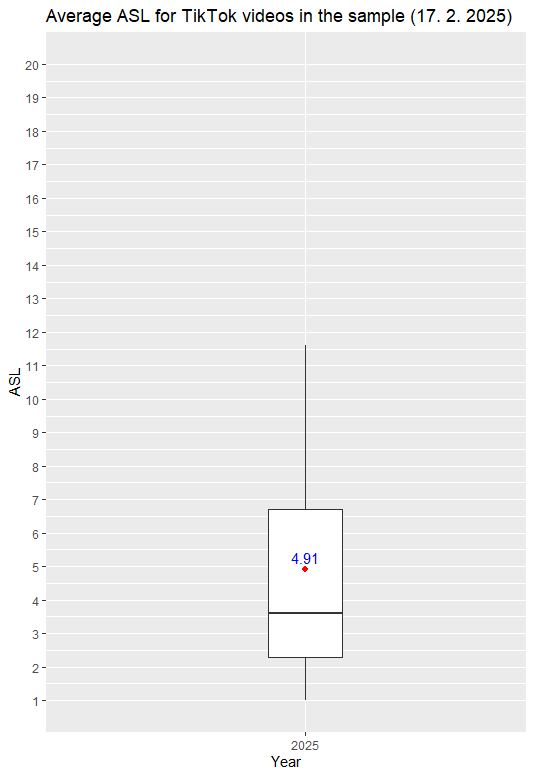

Now let’s see what the average shot length of videos on TikTok is. Admittedly, I don’t have as large a database as Douglas. I collected the data in an unsystematic way one afternoon by sitting down at my desk with TikTok on my smartphone, turning on screen recording, and recording one video from start to finish for about 25 minutes. I then uploaded the file from my phone to my computer and took the classic shot length measurements I’m used to. For each video, I noted the lentg and the number of takes, from which I got the average shot length. In total, there were 19 videos in my sample (including two commercials, two split-screen videos, and five videos that were more like slideshow photographs).

The average shot length of videos on TikTok is longer than the average shot length of American movies. While the median is similar, the boundaries for the third and fourth quartiles are shifted by seconds.

Of course, one could argue that this is due to the sample, and that if I had measured on a different day or in someone else’s recommendation algorithm, I would have gotten different numbers. Sure.

On the other hand, there are arguments that the higher average shot length for TikTok videos may not be accidental. One of the reactions of our eye movement to editing in film is to reorient our gaze to the center of the screen. Research shows that viewers of portrait format videos (which is the format on TikTok) exhibit a weaker central bias than viewers of landscape videos (the format of movies and TV shows). I don’t know what videos specifically the measurements were taken on, but the weaker central bias could indicate a smaller number of cuts after which our gaze turns to the center.

Anyway, I want to repeat the measurements in some time to make sure. For now, I’ll go with the measured data and therefore…

In terms of average shot length, TikTok is simply slower than American movies and TV shows. It is not a fundamental difference, but it is there. When you think about it, it’s not really surprising. On TikTok, many of the videos are shot in one take (I had 6 videos in one take in my sample). These videos will inevitably slow down the TikTok experience and increase the average shot length. But in a way, they are the simplest thing a creator can do and therefore the most typical.

Well, to summarize. Some viewers seem to get the impression of speed from the TikTok videos. This impression is so intense that it has made its way (in a form of intuitive claims) in to academic papers. The problem is that we don’t know how to quantify this impression. For now, the only measurable value is the short duration of the videos, but I don’t think that is relevant evidence of the impression of speed. Especially when the average shot length is higher for TikTok than for the average American film. I therefore put more hope in the amount of information (text + speech) conveyed in the videos, but I’ll leave that for another time.