It’s evening. I’m not going out, but I don’t feel like reading, so I’m watching a movie on an unnamed streaming platform. When choosing, I prefer movies I’ve already seen. Why? So I don’t feel guilty about looking at my phone every now and then.

A not insignificant number of viewers are reportedly thinking along similar lines to this scenario. They watch a film unfocused, or while doing something else. In another post I addressed casual viewing and today I want to look at the changing ways of viewing audiovisual content from the perspective of watching multiple screens simultaneously.

There are several interesting studies on the topic in which researchers have looked at the viewing practice of watching multiple screens simultaneously.

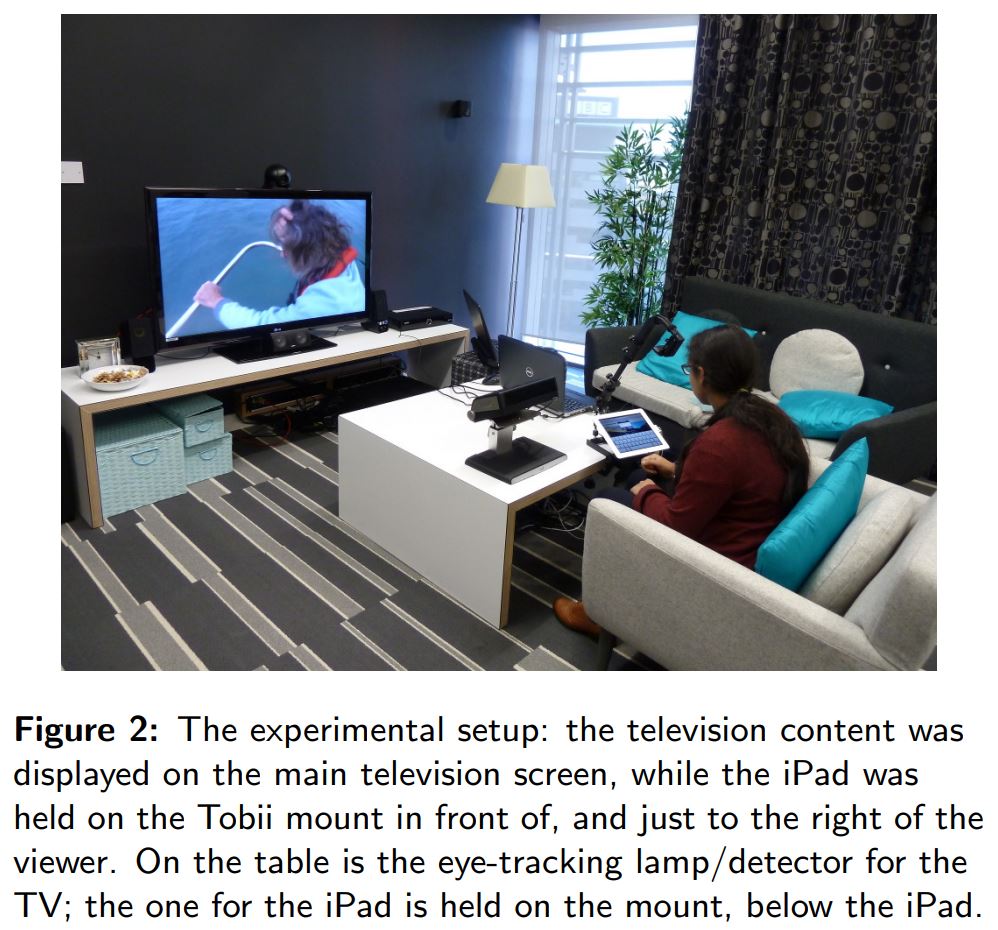

All of the studies are impressive because they experimentally test how viewers behave. They use an eye-tracker (mobile or stationary) and think about setting to resemble a living room as much as possible and a laboratory as little as possible. In other words, they make sure that the experiment reflects the natural environment.

The results are then very compelling and show that viewers are primarily watching TV and paying less attention to the tablet/phone (by a ratio of 2:1 to 5:1).

The problem is that all these experiments are formulated from start to finish in such a way that it is clearly established which screen is “first” and which is “second”. Even the choice of what is played on the second screen is only complementary to what is played on the first screen. For all three studies, this approach is understandable. Their intent was to offer data to make multi-screen viewing consistent, which could then be used by media companies to develop applications. But if we are interested in the relationship between audiovisual and spectator behaviour, we necessarily feel that something has been left out. They left aside the fact that there is a competition for our attention in the media market.

I don’t know anyone who would say they watched TikTok last night and occasionally glanced at what was happening on Netflix. That’s not how we talk about leisure time. Statistics, meanwhile, show that the average U.S. adult in 2024 watched Netflix for only 3.7 minutes longer per day than TikTok (62.1 vs 58.4 minutes). Is that enough of a difference to determine which screen is hierarchically first and second? I’d say no.

It may well be that the attention paid to movies and TikTok is different when the division between first and second screen is abolished. And it’s also quite possible that some movies are less successful at attracting attention (though studies suggest that this is not the case).

I would like to build on the three studies mentioned and think about how to implement experiments in a way that reflects the battle of the screens. To start with, users will need to break the hierarchy of the first and second screens and let them be free.

Leave a comment