In recent weeks, the boom in generative AI models has begun to shift from text and images to video. Anyone can create an eight-second video using Google’s Veo model. Open AI has announced the launch (currently only in North America and by invitation) of a video platform running on the Sora 2 model. In addition, other platforms are emerging that enable the generation of special forms of content, such as micro dramas.

In our family, video generation has become part of our daily bedtime routine. Every evening, the children simply dictate to me what they want their fairy tale to be about. Gemini first prepares the text for me, and after I finish reading it, we generate the video. I consider this to be one of the greatest advantages of generative AI, as the quality of the fairy tales does not depend on how tired I am.

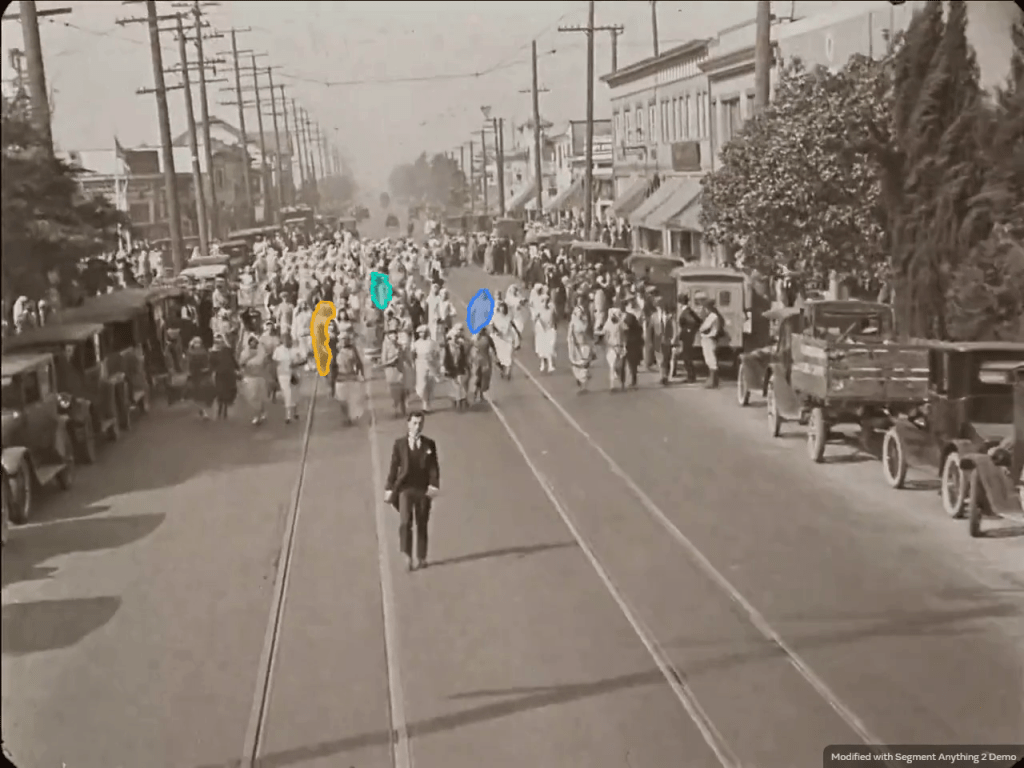

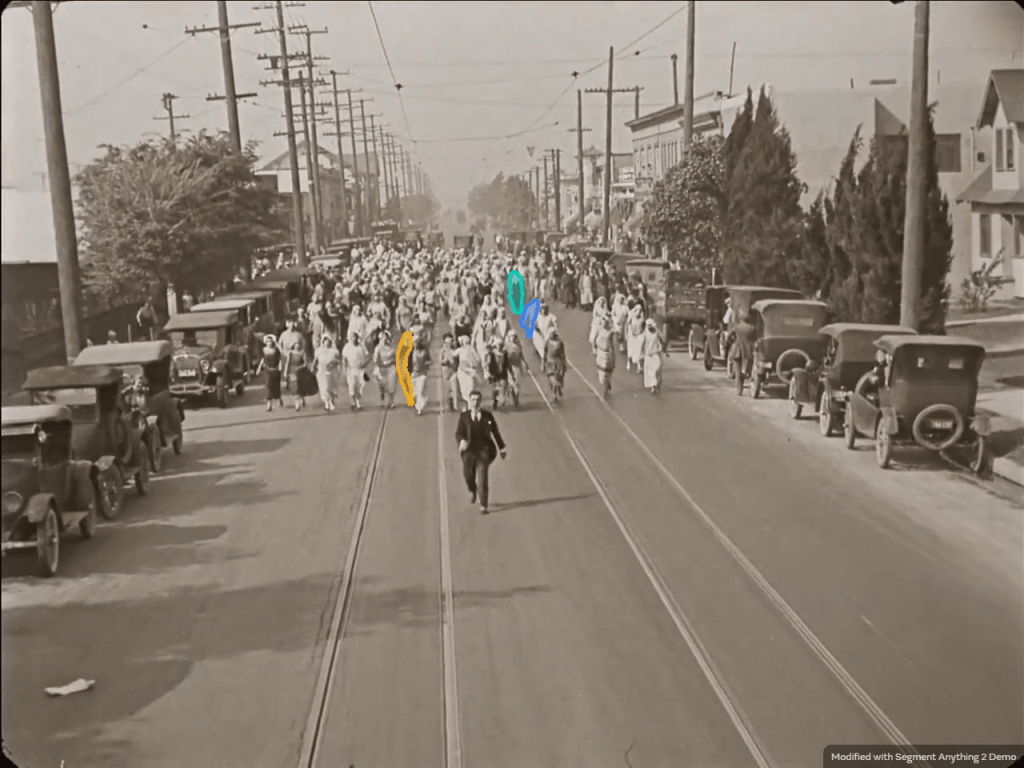

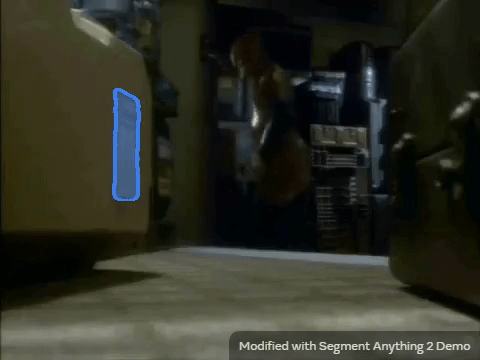

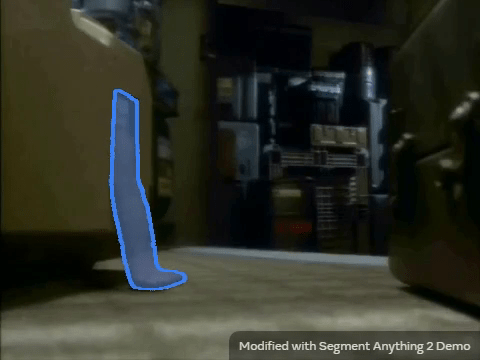

The problem, of course, is that eight-second videos created in two minutes enchant us now, but in a moment we will consider them the norm and they will no longer be enough for us. And if I understand correctly, the problem for developers is still to keep the characters looking consistent between shots, or to ensure that the resulting videos follow basic cinematic continuity rules. This is not surprising, because AI must first learn to tell stories like filmmakers in order to match them, and it took filmmakers decades to do so. And developers could be helped by a traditional institution well known to film historians – the archive – with its tried and tested rules of film storytelling.

I realized this in connection with The Development of Generative Artificial Intelligence from a Copyright Perspective from May 2025, which was brought to my attention by my friend and lawyer Miroslav Obernauer. The creation of a license for training generative AI is being considered. This would solve the problem of the need to train AI on existing works on the one hand and copyright protection on the other.

And this is where there is room for film archives to become centers for training AI, in addition to their role of preservation, restoration, and dissemination.

Take, for example, the Národní filmový archiv in Prague. Archivists care for hundreds of films made in Czechoslovakia – films that could be used to train generative AI. And their collections include thousands more films from other countries around the world.

Of course, I don’t know if this will happen. But I like the idea that an institution such as an archive, which – let’s be honest – is not one of the driving forces behind the digital revolution and does not exactly come across as cool to the public, could find a new role and become integral part of the creation of modern technologies.